Footnote #7: cultural appropriation and the nostalgia trap

tl;dr marketing is fucking powerful, don't let it get ya

Welcome to new subscribers! ✨ I’m pretty sure you’re here because someone shared my tiny screed with you, and your morbid curiosity about the Scandal got you curious. No worries, we do not discriminate here — gossip is welcome, as is your time. If you missed it, here is Part 1.

I started writing Part 2 at the same time I started writing Part 1 of my examination of the most recent cultural appropriation scandal, but finishing P2 honestly took so much out of me. The fire and the ire of that first event has faded somewhat and has left in its place a weariness with this persistent problem of racism and colonialism that we never quite seem to puzzle our way out of.

This newsletter is a bit more fragmented than the last one, but it’s broken up into a number of parts. I talk first about how capitalism-driven cultural appropriation is abetted by nostalgia marketing, then I talk about how the article and SCMP Orientalise specific narratives in attempt to gain money and power. After that, we jump through the false promise of White solidarity with local communities, and end with a small discussion on racial power. Take what is useful, leave the rest.

If you’ve enjoyed reading my essays on cultural appropriation, I plan on writing more works like this in the coming time, so feel free to subscribe to get these right in your inbox.

If you know someone who might be interested in this work, go ahead and forward it to them or share it on your socials. it’s free of both money and the wages of colonialism!

A note on influence-as-money

This was just a thought that I realised I didn’t include in the previous edition but often, when we think about money, we don’t consider Earning Potential as a form of currency. When I say Earning Potential, I am specifically referencing how many influencers (“key opinion leaders” in marketing jargon) or thought-leaders 🤢 are imbued with a form of social currency that may look like being considered an authority on a subject, which might lead to being quoted or featured in a publication; or a vessel of public trust.

In a world where commerce is increasingly mediated by social networks, this social currency is well-understood if under-acknowledged as a key ingredient for Hard-Cash Earning Potential. Money is always waiting to made and influence is its vehicle. So many individuals with aspirations to becoming influencers have a vested interest in cultivating their reputations as an authority on X subject in order to eventually cash out via brand partnerships or sponsorships.

I’m most familiar with this in the yoga world, so here’s a fun thing to do: if you start noticing a friend or teacher doing “7 Tips to Achieve X Pose” type posts, that’s a good indication that they are beginning to build up their image/following in order to pitch or catch the attention of brands.

Considering how Whiteness — and to a similar extent, Westernness — is particularly prized in Southeast Asia, influencers from these intersections have a market advantage. Brands in the Klang Valley are more likely to engage with them because they speak directly to their ideal customers: educated overseas, highly attuned to Western media, aspirational.

Many local brands are also countering this by actively engaging with local talent, but without sufficient data on this, it’s hard to say what the proportions are. But it’s obvious why companies and advertisers insist on a “pan-Asian” look in their talents, especially if their English is inoffensively placeless. They are hoping to cash in on proximity to Whiteness and Westernness.

So while you don’t have to be White to earn money through social currency, it certainly helps — it’s easier to make it as an influencer in Asia if you’re White, more so if you’re pretty and cash into specific niches (yoga, travel, food, etc. you get it). If you’re White here, it’s likelier you be at least tangentially associated with the affluent and influential circles — the tech-bro imports; brunch-moms in Kenny Hills; international school parents; or the social networks that orbit European diplomats — that can help your already-extant racial power go further in the world.

And in effect, that racial and colonial power helps you earn more money.

Part 2: the nostalgia trap

If there is a specific part in the South China Morning Post article on Ms Scheers which I thought about most, it’s the bit about the pink minibus:

“I remember I went to school on a pink minibus. You just jumped on and jumped off again. It was also a time before the internet. My father would finish work every day at five and go and play polo. In those days it as just different. That kind of lifestyle isn’t possible anymore.”

What struck me about those words was just how much they are imbued with the vivid tunnel-vision of a child, decontextualised and placeless. It makes me think of one of those old View Master stereoscopes loaded with a photo reel of “Southeast Asia” that you can flip through: pink school bus. The blurred arc of a leap. Polo game on a lawn, everything coated in warm sepia tones, or gently smeared technicolour.

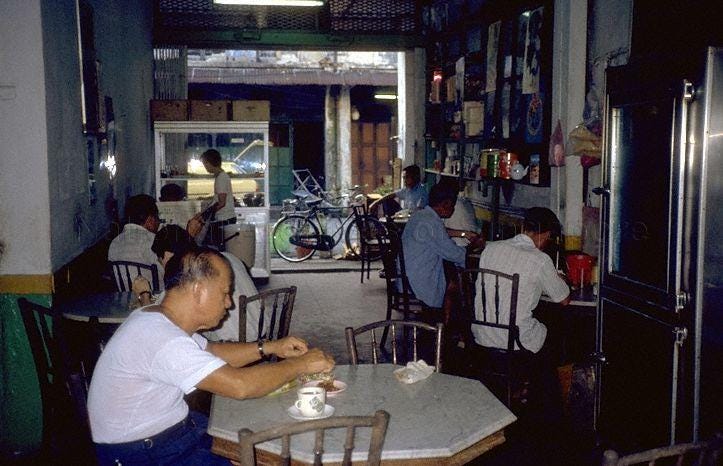

Do you know what I think about when I think about Kuala Lumpur and buses? I think about cramped spaces and body odour. I think of useless timetables. I think of disconnected arteries, joined ineffectually by covered walkways and disparate systems. I think about those old photos of Kuala Lumpur after the ’69 race riots: wrecked, turned-turtle, burning.

The SCMP story feels familiar because it plays into theme common to many historical novels about colonial life: I am thinking of books like Passage to India, Anthony Burgess’s Malayan Trilogy, Tash Aw’s Harmony Silk Factory, and all those Lisa See books. These narratives are fantastical and they hold a lot of appeal for their lushly written prose and plots packed with personal and political drama. This is a genre of story that has a well-established market both internationally and locally.

However, it’s also a genre with a well-documented disinterest in historical fact, and a deeply-rooted fascination with nostalgia and a big helping of fantasy. All of which come together in heady, dangerous mixture. In Ms Scheers’ accounting of Kuala Lumpur, the city is all pink minibuses, old racecourses, Peranakan ceramics and friendly calligraphers. It had a small-town vibe that made her feel safe to walk the city as a child, a lifestyle she says “isn’t possible anymore.”

I’d like to pause for a moment here and say that this lifestyle wasn’t possible for most people, past or present.

The tone of the account is presented is casual to the point of eliding evidence of immense wealth. Presented without context or consideration, it assumes her version of events as the default, and disguises the fact that this kind of life was built atop a mountain of privileges confined to a (very) small coterie of upper crust families and individuals: education, sports, travel, pocket money and — most tellingly — safety.

Imagine feeling safe in a pre-smartphone Kuala Lumpur!

Academic Stephanie Coontz wrote in 2018 about how the nostalgia trap “involves a denial of the racial, ethnic, and family diversity of the past, as well as its social injustices, creating romanticised myths that are easily refuted by anyone willing to confront historical realities.”

If we are to confront the “historical reality” of life in Kuala Lumpur in the 80’s, you won’t get the saccharine fairytale presented to us in the article. You’ll get something infinitely more complex, more dangerous, more diverse, more poor.

Kuala Lumpur in the 80’s was a city just a decade out from the ’69 race riots, a mixture of suburb, skyscraper and village that housed a local urban population just beginning to edge out of poverty towards lower middle-class status. Here was where the first “hostels" were being set up in the shadow of Najib’s phallic vanity project, the TRX, a preamble to the full-to-brimming tenements used to “house” the brown migrant workers who would begin building this already-crumbling city. This was a Kuala Lumpur cracking under the pressure of the NEP, and watching the rise of Mahathir. A Kuala Lumpur more brown than they would have you believe; full of poor people who needed the work available in a city that was becoming increasingly expensive and globalised.

The Kuala Lumpur offered to us in that interview — or by any of those historical fantasy novels — was never real, and any desire to return to it is cosplay at best, disingenuous at worst. If anyone felt safe here, it was because they had the privilege to do so. To live cloistered from the lives led by people who didn’t have the protections of money, family and colour.

If cultural appropriation is about non-locals taking local cultures and bastardising them for monetary gain, then there necessarily exists an underlying incentive to maintain control over the narrative of the market in which your product is sold. The appropriator has a vested interest in creating a demand for a product by tapping into any one of the many emotional buttons that drive consumption.

In the case of Nala, there is a vested interest in pushing a specific vision of old Malaya in order to elicit specific feelings within customers, usually ones associated with childhood. A simpler, more quaint time, when the world was revolved around family meals, play, tea and toast, maybe a particular idea of Malaysian unity. You can practically hear the P. Ramlee music overlaid as the vision scrolls past.

This, my friends, is what we call “nostalgia marketing”, a well-worn tactic by advertisers designed to trap you with familiarity. Our government and biggest advertisers frequently makes use of this trope by calling up ghosts from the past, warm and fuzzy national myths (Malaysia claimed our independence!) and collective symbols of the good ol’ days (think Milo trucks, and sports days).

A good example are the Petronas ads that get cycled out every year with such regularity, you can set your calendars to them. They were so popular, they managed to launder the reputation of the country’s biggest contributor to climate change and spurred the growth of a cottage economy for festive ads that have since powered the careers of certain local filmmakers.

Nostalgia marketing is powerful because it makes people feel good, but also because it creates a veneer of perceived authenticity. Ms Scheers’ story may be familiar to many people because it has just enough detail to ping something in their hippocampus, but vague enough to allow you fill in the dots yourself. That collaborative form of myth making is what lends Nala’s narrative its sheen of authenticity and authority which ultimately manifests itself as market advantage.

The brand must insist on this glamorous, fake version of the past in order to make its product relevant and appealing. And it would behoove all of us to remember that Ms Scheers was herself a successful marketer.

the narrative is racist

I place some blame here at the feet of SCMP. Where were the interviewer questions? Why wasn’t there any sense of editorial judgement. Thomas Bird, whose byline is on the article, doesn’t do anything to probe the perspective brought by Ms Scheers, neither does he contextualise the world for his readers, many of whom are presumably not Malaysian. He, unlike Ms Scheers, has not said anything with regards to the backlash online.

Frankly, it feels like they threw her under the bus.

But that aside, the article relies on a specific trope common to Western journalism: life in the Oriental wilderness, as seen through the eyes of one their (White) own. This type of lens always Others the world around them while simultaneously elevating the judgement of its narrator or its White mouthpiece. Its racism is subtle because it’s so self-contained within its constructed reality, narrowly pinning the reader into the aesthetics of a travel guidebook from the 40’s.

From Edward Said’s Orientalism: “Orientalism is premised upon exteriority…the Orientalist, poet or scholar, makes the Orient speak, describes the Orient, renders its mysteries plain for and to the West. He is never concerned with the Orient except as the first cause of what he says.”

Put simply, the Western journalist parachuting into exotic Southeast Asia doesn’t actually care about what the region and its peoples have to say for and about themselves. In the Orient, the Orientalist’s eye only sees raw material for inspiration; flat metaphors or symbols for the Big, Important Thoughts he or she may have about life or the world. The Orient, in their eyes, lacks individual complexity, history or complex culture, qualities which can only be conferred upon them by the White Saviour or Translator.

Much in the same way White Woman In Asia Chic decontextualises local fashions and cultures in order to sell its costly knockoffs, Orientalist narratives limit foreign cultures into specific images which are redefined without the input of local communities (as Said says: “makes the Orient speak”), before reselling the narratives back to their readers at home as something “new”, like tchotchkes sold at airports.

In this model, Ms Scheers’ Petaling Street, full of costumed calligraphers and Peranakan ceramics, aren’t presented as what they really are — blatant products of the tourism economy — but as a cheery memory, more vibrant and cultured than what currently exists.

This is a recurring narrative that has become a trademark for South China Morning Post’s English language lifestyle section (again, for transparency, just highlighting that I’ve contributed to SCMP before). The Hong Kong-based newspaper is one of the biggest in the region, whose lifestyle section is catered largely to English-speaking expat communities who populate big expensive cities like Hong Kong, Singapore, Ho Chi Minh, Manila and, yes, Kuala Lumpur. Many, but not all, are White — most, if not all, are rich.

For the publication, interviews like these create the needed texture of human interest stories that soften the hard-news angles that tend to dominate papers. Human interest stories are where money gets made, and in the case of SCMP, it expands the net of their audiences (customers) beyond their Hong Kong base.

It all comes back to money: it is in the paper’s best interest to continue peddling stories where they have the authority to “demystify” a region one of their readers might like to travel to — coincidentally, we do have a coupon for you book a stay at this four-star hotel in Bangkok!

In the same way a brand like Nala might need to sell a nostalgic vision of Malaysia to sell their nostalgia-inspired products, it makes perfect economic sense for SCMP to set the terms of the world so you may explain it, a fundamentally colonialist impulse.

White colonists impose their language on the oppressed as a form of control: if you can name it, you can categorise it; if you can categorise it, you can explain it. If you can explain it — if only you can explain it to your powerful friends in the West — then you are an authority, and you may sell that authority to the highest bidder. You are king over all you survey.

Make no mistake that in this, the editors of this ostensibly Asia-forward paper have no interest in being in solidarity with the rest of us. We are not their audience.

Because if you, my dear Other, think about it — like really think about it — think about the tone-deafness, the silence, the choice to highlight this person as an authority on life in Malaysia — then you cannot possibly imagine that this was meant for you.

the myth of white solidarity

Why does a White woman’s account of life in Malaysia get raised to the level of an international publication, and not those of a local? I know that for SCMP, Ms Scheers’ adolescence and life here, placed neatly at the forefront of the article, is meant to lend her the air of authority: she grew up in Malaysia, so of course she can speak to what it means to live life here! She’s practically Malaysian herself!

But look closely at the vision the article inscribes: a half-baked, unreal world that is more fake than anything you could buy on Petaling Street.

The narrative of a world these White people want to “save” is so ludicrously far from everyday people’s reality that it serves only to obscure the actual problems that are faced here. Consider that when that American lady in Bali said that the island was welcoming to queer people, her narrative — which, by virtue of being Western, is ranked higher and heard more loudly than any local Balinese person’s — she is erasing the actual dangers faced by LGBT folks from view (and therefore, existence).

By claiming that Malaysians are only hyper-focused on the piecemeal commercialisation of its heritage and art, Ms Scheers and her cohort are erasing from view not just the efforts of local art-makers in Kuala Lumpur, but are also ignoring the very real problems that are affecting local art: hostile government policies, high costs of living, rampant urbanisation, the suppression of workers’ wages, racism, misogyny.

It’s easy to point out the problems if you don’t see yourself responsible for fixing them.

White people in Asia are always proclaiming solidarity with the people in their host countries, but they never see themselves as part of the rot they deride. They don’t see themselves as being complicit in perpetuating stale narratives or actively involved in creating them. They never see how their presence drives up the cost of living, drowns out local voices — how they take up so much space just by virtue of being White and Western.

How could they? By and large, White expats are mostly disconnected from the local communities of their host countries, geographically, linguistically and culturally. And even when they are connected, there is a palpable recalcitrance to learning and understanding their adopted homes.

White privilege here is not having to learn a language or bend to the customs of a place. You simply expect the world to bend to you.

In Part 1, I talked about how White people don’t see themselves in the language of commerce because they are above it. They also do not see themselves in the language of power because they are so accustomed to having it that the opposite has probably never occurred to them. They refuse to see the inner workings and obfuscations of the power they wield as White people. They just think their race is a matter of nature, empty of meaning. They have deluded themselves into thinking that their Whiteness isn’t itself a kind of race, and subconsciously, that Whiteness is the default.

They’re surprised when their tone-deaf, racist remarks are not welcomed with open arms and invite legitimate criticism, and are then abetted by local supporters who have also drunk the it’s not about race! Kool-Aid. Imagine being privileged enough to forget that it is always about race.

The thing is, dear reader, if White people are made to see their race as power — if we are forced to confront our own complicity in helping them ignore their racial power — then they have to reckon with the guilt around old, untended wounds. Colonial wounds. Racial wounds. Wounds with a price tag.

It is in their interest to maintaining that their Whiteness has no politics because when crucial conversations are stripped of the weight of racial politics, they can ignore the very real repercussions that institutionalised racism has enacted on real people without the safety nets of money and connections. They can ignore their role in perpetuating the systems, or remaining complacent.

We can all ignore the difficult, messy work of actually reckoning with collective pain, past and present.

Colonialism isn’t just about stripping the oppressed of meaning and identity, it is also about absolving the self of responsibility for ending it.

I just want to be clear that I don’t blame Ms Scheers or White people for everything: they are not responsible for corrupt politicians, bad policy, the class tensions that tighten around the country like a noose. But they are responsible for the power they wield. How they choose to use it, or not. And if they (you) choose to wield it responsibly, then don’t just sit there. Do something about it. Make a goddamn difference. Then we’ll talk.

Until next time, beloveds.

Yours from the void,

Sam.